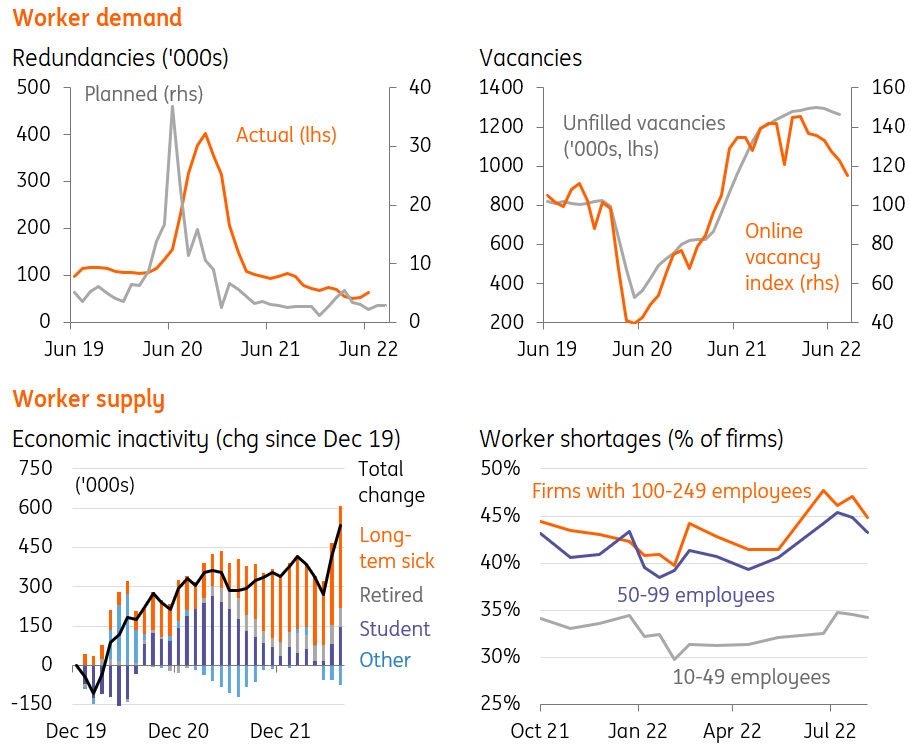

The number of workers classified as long-term sick has jumped dramatically in the past couple of months, and that’s one reason why firms are still struggling to source the staff they need. While worker demand has cooled, Bank of England hawks will be worried that these shortages will continue to push up wage growth

At a headline level, the latest UK jobs numbers don’t look too bad. fell by two-tenths of a per cent to 3.6%, the lowest level since 1974. But this is driven not by an increase in the number of people in employment, but primarily by another dramatic rise in those classified as inactive – that is neither in work nor actively seeking it. Alarmingly, the number of people classifying as not working due to long-term sickness is up by almost 400,000 since late 2019, and almost 150,000 in the last two months’ worth of data alone. It’s hard to escape the conclusion that this is linked to the pressures in the National Health Service (NHS).

The Bank of England will view all of this through the lens of the worker shortages that have plagued the jobs market for the past year or so. While some causes of that shortage appear to be abating – e.g. inward migration of non-EU workers has increased noticeably this year – other factors are, if anything, getting worse. A look at the survey evidence suggests firms are finding it no easier to find staff than they were a few months ago either. Both the BoE’s Agent’s survey and the ONS’ bi-weekly business survey have shown no improvement in the number of firms saying they are struggling to source workers.

U.K. jobs market dashboard

Worker shortages is taken from a question in the ONS bi-weekly business survey

At the same time, demand for employees does appear to be cooling, though not necessarily very quickly. The level of job vacancies has fallen from its high, but the number of redundancies is low and stable (even if the level increased slightly in this latest data). The question now is whether the pressure from energy prices will force companies to revisit these plans and make more material changes to their workforce. We would expect a more visible impact on the jobs market over the next few months, but the government’s newly-announced pledge to cap corporate energy bills as well as households’ should help avoid a sharp rise in unemployment this winter.

Persistent worker supply constraints coupled with so far only modest signs of reduced hiring demand will provide further ammunition for Bank of England hawks to push ahead with further tightening. We expect a 50 basis-point rate hike next week, and another in November. While markets may be overestimating how far the Bank will take interest rates over the coming months, we think the BoE is less likely to be cutting rates early into 2023 than some other global central banks.

Disclaimer: This publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user’s means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more

Original Post