If we’re generous, the case for arguing that inflation has peaked is mixed. Depending on the indicator of choice, there’s supporting evidence for deciding that worst of the inflation surge is behind us. But there’s also data to assert the opposite, as yesterday’s update on consumer prices reminds.

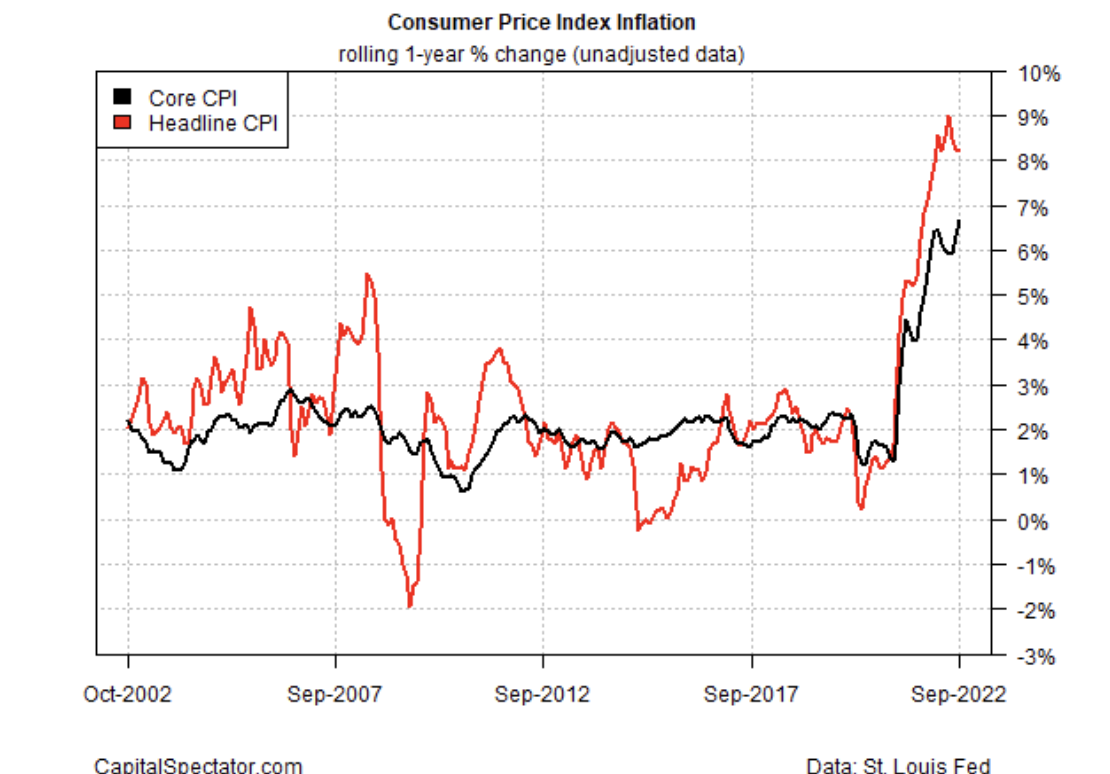

The CPI numbers for September is a study in contrasts. Headline continues to show peak inflation in the rear-view mirror, if only modestly, but core inflation continues to rise to new heights. The Federal Reserve focuses on core inflation for several reasons, including the empirical evidence that it tends to offer a better estimate of the trend compared with higher short-term volatility of its headline counterpart. On that basis, the ongoing rise in is a new warning that inflationary pressures haven’t peaked yet.

Core CPI rose to 6.6% on an annual basis (in unadjusted terms) through September, edging above the previous top in March and thereby reaching a 40-year high.

Sal Guatieri, a senior economist at BMO Capital Markets, says:

“This is not what the Fed wants to see six months into one of the most aggressive tightening cycles in decades.”

The CPI report suggests that the Fed will continue to raise rates aggressively. Fed funds futures are currently pricing in a near certainty of another 75-basis-points hike at the next FOMC meeting on Nov. 2.

Ajay Rajadhyaksha, global chair of research at Barclays, says:

“There is a persistence in inflation that if you are the Fed has got to be deeply worrying. Most people have felt like we are just about to turn, whether it be on jobs or on inflation, and it doesn’t happen and it doesn’t happen and it doesn’t happen.”

The Financial Times reports that Rajadhyaksha expects the Fed will extend 0.75 percentage point rate hikes through the end of this year and start to slow the hikes to a 0.50 percentage point increase at 2023’s first meeting in early February.

Is the case for peak inflation dead? No, at least not entirely, although the timing remains unclear. There are numerous encouraging signs, ranging from easing tightness is key supply chains to softer price increases in some shipping costs. Michael Pond, Barclays (LON:) head of global inflation-linked research, predicts signs of peak inflation will strengthen in the months ahead.

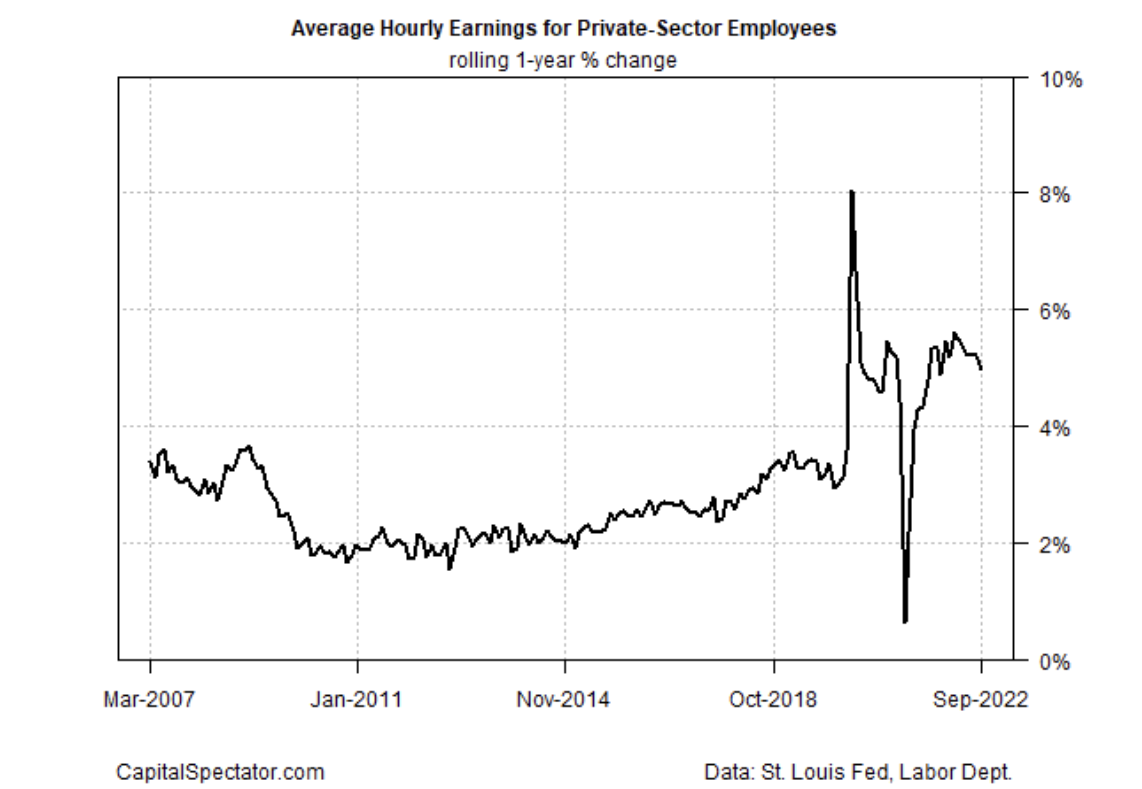

Wage inflation suggests as much. The annual increase for the average hourly earnings of all private employees has turned lower recently, slipping to 5.0% through September, the slowest this year.

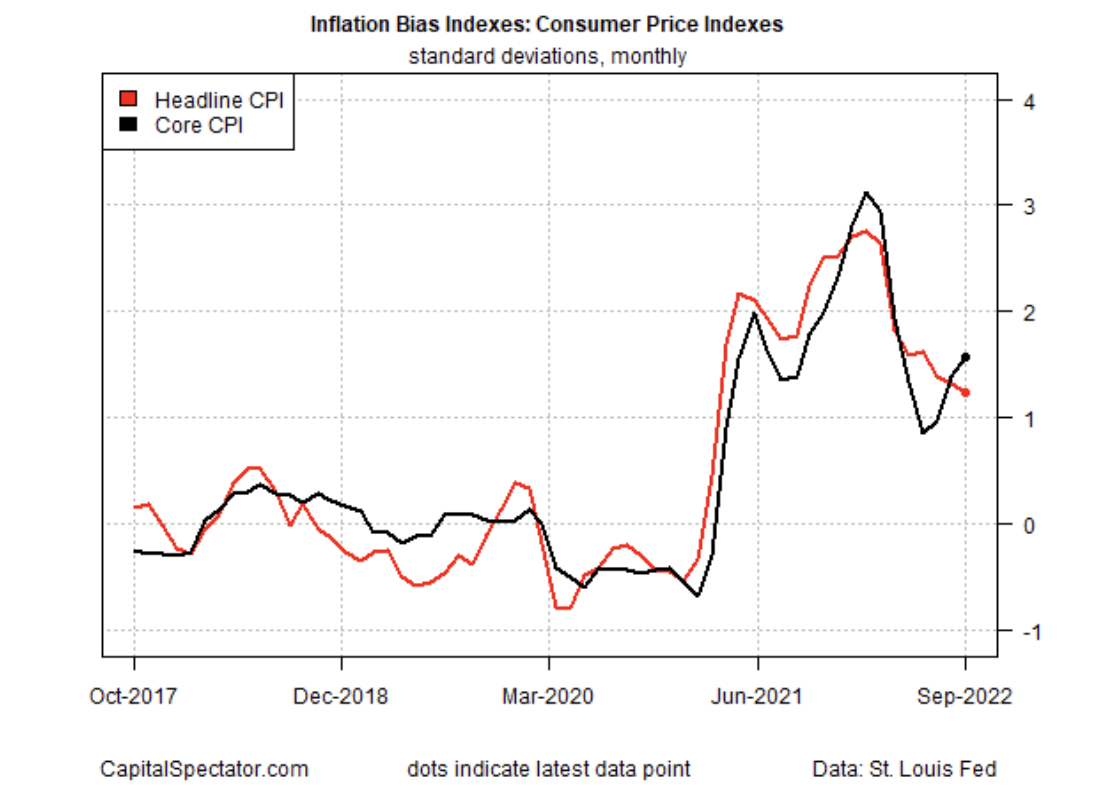

But the recent divergence in core vs. headline CPI measures remains in sharp relief, which makes a strong case for reserving judgment. Profiling the data via CapitalSpectator.com’s Inflation Bias Indexes makes this clear by way of the recent upturn in core CPI. It’s unclear if this is noise that will soon resume the downward bias that had been persistent until recently. (The methodology takes a standard inflation index, calculates the one-year change and then computes the monthly difference and transforms the results into standard deviations around the mean. This measure offers a way to develop some quantitative insight for deciding which way the inflationary wind is blowing.)

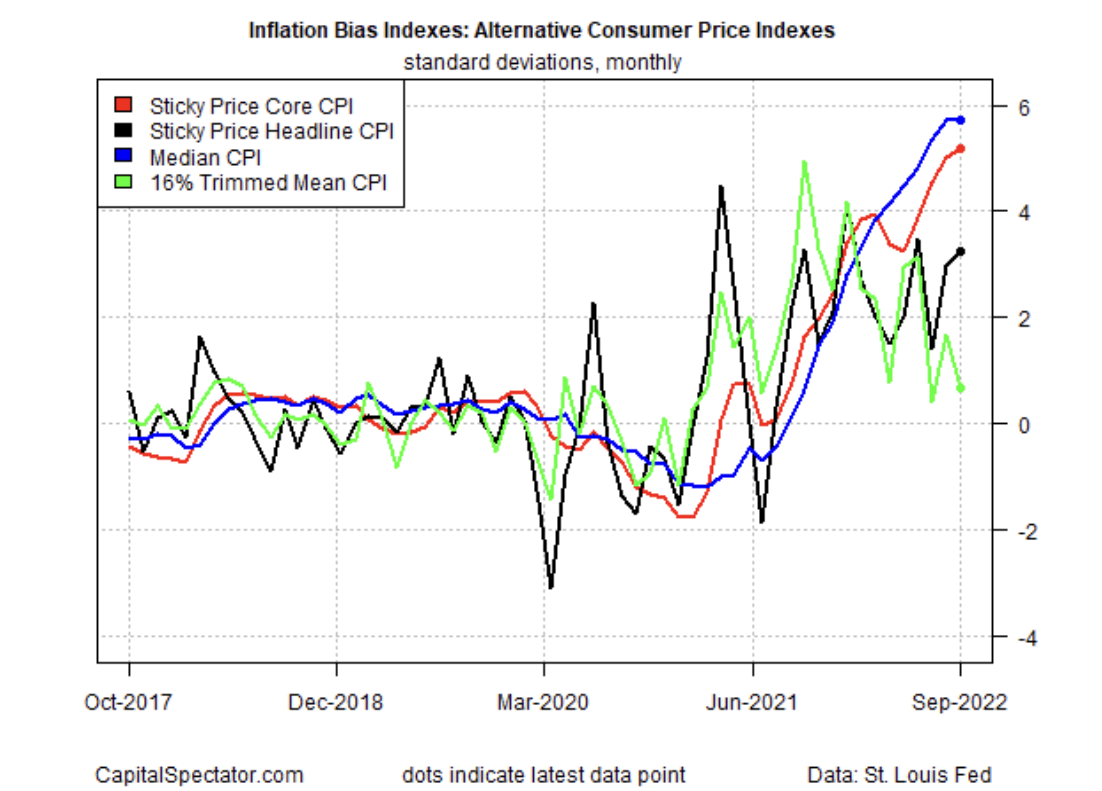

An alternative (and arguably more robust) set of consumer inflation measures paints a stronger case for expecting that the inflation bias is still skewing higher (based on reviewing the data through CapitalSpectator.com’s inflation bias methodology noted above). Three of four of these measures point to an upward bias for inflation.

As I noted in last month’s , the alternative inflation metrics continue to suggest that high inflation is looking more entrenched, which in turn will likely spur the Federal Reserve to raise rates further for longer, and perhaps in bigger-than-recently expected increments. That was true a month ago and remains true following the release of September data.

Nonetheless, relief may be near, albeit for reasons that are hardly comforting. As I last week, the economy appears set to fall into a recession starting in November. If correct, a hefty dose of inflation taming may be near. That’s a harsh dose of medicine, but history suggests it almost always works… eventually.